The body is a unit, though it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body. So it is with Christ.13 For we were all baptized by one Spirit into one body--whether Jews or Greeks, slave or free--and we were all given the one Spirit to drink.14 Now the body is not made up of one part but of many.15 If the foot should say, "Because I am not a hand, I do not belong to the body," it would not for that reason cease to be part of the body. 16 And if the ear should say, "Because I am not an eye, I do not belong to the body," it would not for that reason cease to be part of the body. 17 If the whole body were an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? If the whole body were an ear, where would the sense of smell be? 18 But in fact God has arranged the parts in the body, every one of them, just as he wanted them to be.19 If they were all one part, where would the body be? 20 As it is, there are many parts, but one body.21 The eye cannot say to the hand, "I don't need you!" And the head cannot say to the feet, "I don't need you!" 22 On the contrary, those parts of the body that seem to be weaker are indispensable, 23 and the parts that we think are less honorable we treat with special honor. And the parts that are unpresentable are treated with special modesty, 24 while our presentable parts need no special treatment. But God has combined the members of the body and has given greater honor to the parts that lacked it, 25 so that there should be no division in the body, but that its parts should have equal concern for each other. 26 If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it. 27 Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it.28 And in the church God has appointed first of all apostles, second prophets, third teachers, then workers of miracles, also those having gifts of healing, those able to help others, 1 Corinthians 12:12-28a (NIV)

Body of Christ

The body metaphor for the people of God is a powerful image that bespeaks the new historical reality brought about in Christ. It surfaces in only four New Testament epistles, but in a bewildering array of associations.

Relational Unity in Romans and 1 Corinthians Romans (12:4-5) and 1 Corinthians (10:17; 11:29; 12:12-27) reflect an earlier stage of usage. Paul's fullest treatment of the theme ( 1 Co 12:12-27 ) consists of an extended comparison between the human body (soma [sw'ma]) and the church in order to emphasize horizontal union among the members of Christ's body and to demonstrate dramatically both diversity within unity (12:12a, 14-19) and unity out of diversity (12:12b, 20-27). A church that was well known both for the giftedness of its members ( 1 Co 1:7 ) and its toleration of divisions ( 1 Cor 1:10-13 ; 3:3 ; 4:6 ; 6:6 ; 11:17-22 ; 12:25 ) needed to heed warnings against both groundless inferiority (12:14-19) and disdainful superiority (12:21-25). Each member of the body has an important (vv. 17, 22), although not always glamorous (vv. 23-24), contribution to make, and no member experiences humiliation or honor without somehow affecting the rest (v. 26 cf. 2 Cor 11:28-29 ).

Similar injunctions come in Romans 12. Instead of displays of arrogance (vv. 3, 16), each member of the body is called to employ his or her gift(s) in brotherly love (v. 10), recognizing both the diversity (vv. 4-5a) and the unity (v. 5b) that define their place in Christ. For Paul, the urgent need for humility, interdependence, and love within the Christian community is grounded in this dynamic horizontal unity between members of the body of Christ, a union that overcomes even the most imposing racial and social barriers ( 1 Cor 12:13 ; cf. Gal 3:28 ; Eph 2:16 ). But it is not at all clear that Paul took up the body metaphor simply as a memorable way to describe relations within the community. Horizontal, social relations between members are grounded in the vertical union each member enjoys with Christ ( Rom 12:5 ; 1 Cor 10:16-17 ; 12:13 ). That body of Christ language could apply both to the local congregation ( 1 Co 12:27 ) and to something more universal ( 1 Co 12:13 ) not only attests to the flexibility of the metaphor but also reflects an important element in Paul's ecclesiology: the local church is a localized manifestation of the church universal ( 1 Cor 1:2 ; 2 Cor 1:1 ).

Union with Christ in Ephesians and Colossians Ephesians and Colossians reflect a further stage of development. The imagery shifts from horizontal unity among members (one out of many) to vertical union with Christ (the many in the One). No longer is the head merely one body part among many, but Christ's role as head over the church entails organic unity ( Eph 4:15-16 ; Col 2:19 ), authority and supremacy ( Eph 1:22 ; 5:24 ; Col 1:18 ), self-sacrifice ( Eph 5:25 ), origination ( Col 1:17-18 ), provision of life ( Col 2:19 ; 3:3-4 ), and enablement of growth and sanctification ( Eph 4:16 ; 5:26-30 ; Col 2:19 ). Moreover, this head-body relationship between Christ and the church stands at the center of God's plan for the entire cosmos over which Christ has been established as sovereign ( Eph 1:20-23 ). But whereas Christ fills the cosmos in terms of his ultimate sovereignty, he fills his body, the church, as he supplies power (1:19), infuses life (2:5), secures exaltation (2:6), and showers kindness (2:7). Only the church is called Christ's fullness (1:23), and as the body of Christ, the church shares Christ's exaltation and session at God's right hand in the heavenly places ( Eph 1:20 ; 2:6 ).

Related Themes and Possible Influences Attempts to identify the background and antecedents of New Testament body imagery have not been totally successful. Least likely influences include Gnostic mythology (Schlier, Kä emann, Bultmann), ancient political theory (which drew parallels between the city or state and the human body; E. A. Judge, F. Mssner, W. L. Knox; J. C. Beker), and rabbinic speculation about the nature of Adam's body (W. D. Davies). Luke's description of Paul's experience outside Damascus ( Acts 9:4-5 ) suggests a close association between the exalted Jesus and his followers on earth, but actual "body" language is entirely absent. Similarly, Old Testament portrayals of God as bridegroom and Israel as bride do not stress unity nor do they portray the marriage as a "one flesh" relationship. And even when Christ's roles as head and bridegroom of the church converge ( Eph 5:23-32 ), the metaphors function independently.

A stronger case can be made for the influence of the Old Testament principle of corporate representation (Ridderbos, Clowney). If a representative could act on behalf of his group, it would be natural to identify the group with that representative. (H. W. Robinson's more complex notion of corporate personality, which all but obliterates the sense of individuality in ancient Hebrew culture, should finally be laid to rest.) Clearly, the New Testament ties the destiny of God's people to the faithful and selfless act of Messiah, and identification with Christ in his death is indispensable for Paul ( Rom 6:8 ; Gal 2:20 ; 5:24 ; and his "in Christ" formula ). Nevertheless, clear indications that Old Testament representation was the formative influence in Paul's concept of the body of Christ are lacking. Indeed, the idea that the one can represent the many is not at all limited to Hebrew culture (M. Barth, Ephesians, 195f.; S. Porter, 298). In the end, it is best to imagine Paul enlisting various themes and background ideas while forging a unique and versatile metaphor that served his own ecclesiological and christological purposes

The Church and the Death of Jesus Significantly, in both 1 Corinthians and Ephesians, the metaphorical body of Christ is tied tightly to the physical body of Jesus in its death on the cross. Jesus' body is represented by the bread of the Eucharist ( 1 Cor 10:16-17 ; 11:29? ) so that those who share the single loaf of communion constitute a single body; their actions demonstrate both corporate inclusion into Christ and their membership in the Christian community that Christ's death brought into existence. But it is connection to Christ and his death that establishes connection to his people. In Ephesians, the bodily death of Jesus on the cross is what abolishes the enmity between Jew and Gentile (2:13-15), and replaces it with reconciliation and unity (2:16). Whether in one body (en heni somati) refers to the physical, bodily death of Jesus or, more likely, to the church that constitutes a unity, the effect is accomplished through the cross. And Christ's role as Savior of the body (5:23) is explained in terms of his sacrificial death on behalf of the church (5:25; cf. 5:2). In Colossians, the relationship between the physical death of Christ and the church as the body of Christ is less explicit, but foundational nonetheless (1:18-24; 2:12-3:4). The redemptive work of Christ, accomplished bodily on the cross, established unity among God's people. To call those people the body of Christ was to highlight dramatically the event and the person responsible for their very life and final destiny.

Bruce N. Fisk

See also Church, the

Bibliography. R. Banks, Paul's Idea of Community; J. C. Beker, Paul the Apostle: The Triumph of God in Life and Thought; E. Best, One Body in Christ; E. P. Clowney, Biblical Interpretation and the Church: The Problem of Contextualization; W. D. Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism; R. Y. K. Fung, EvQ 53 (1981): 89-107; R. H. Gundry, Somain the New Testament; A. T. Lincoln, Paradise Now and Not Yet; P. S. Minear, Images of the Church in the New Testament; S. E. Porter, SJT43 (1990): 289-307; H. Ridderbos, Paul: An Outline of His Theology; H. Rikhof, The Concept of Church: A Methodological Inquiry into the Use of Metaphors in Ecclesiology; H. W. Robinson, The Christian Doctrine of Man; J. A. T. Robinson, The Body: A Study in Pauline Theology; R. Schnackenburg, The Church in the New Testament; E. Schweizer, TDNT, 7:1067-80.

Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Edited by Walter A. Elwell

Copyright © 1996 by Walter A. Elwell. Published by Baker Books, a division of

Baker Book House Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan USA

Church, the [T]

Definition of the Church. The New Testament word for "church" is ekklesia [ejkklhsiva], which means "the called out ones." In classical Greek, the term was used almost exclusively for political gatherings. In particular, in Athens the word signified the assembling of the citizens for the purpose of conducting the affairs of the polis. Moreover, ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] referred only to the actual meeting, not to the citizens themselves. When the people were not assembled, they were not considered to be the ekklesia [ejkklhsiva]. The New Testament records three instances of this secular usage of the term ( Acts 19:32Acts 19:39Acts 19:41 ).

The most important background of the term ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] is the Septuagint, which uses the word in a religious sense about one hundred times, almost always as a translation of the Hebrew word qahal [l;h'q]. While the latter term does indicate a secular gathering (contrasted, say to eda [h'de[], the typical Hebrew word for Israel's religious gathering, and translated by the Greek, sunagoge [sunagwghv]), it also denotes Israel's sacred meetings. This is especially the case in Deuteronomy, where qahal [l;h'q] is linked with the covenant.

When we come to the New Testament, we discover that ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] is used of the community of God's people some 109 times (out of 114 occurrences of the term). Although the word only occurs in two Gospel passages ( Matt 16:18 ; 18:17 ), it is of special importance in Acts (23 times) and the Pauline writings (46 times). It is found twenty times in Revelation and only in isolated instances in James and Hebrews. We may broach the subject of the biblical teaching on the church by drawing three general conclusions from the data so far. First, predominantly ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] (both in the singular and plural) applies to a local assembly of those who profess faith in and allegiance to Christ. Second, ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] designates the universal church ( Acts 8:3 ; 9:31 ; 1 Cor 12:28 ; 15:9 ; especially in the later Pauline letters, Eph 1:22-23 ; Col 1:18 ). Third, the ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] is God's congregation ( 1 Cor 1:2 ; 2 Cor 1:1 ; etc.).

The Nature of the Church. The nature of the church is too broad to be exhausted in the meaning of the one word, ekklesia [ejkklhsiva]. To capture its significance the New Testament authors utilize a rich array of metaphorical descriptions. Nevertheless, there are those metaphors that seem to dominate the biblical picture of the church, five of which call for comment: the people of God, the kingdom of God, the temple of God, the bride of Christ, and the body of Christ. The People of God. Essentially, the concept of the people of God can be summed up in the covenantal phrase: "I will be their God and they will be my people" (see Exod 6:6-7 ; 19:5 ; Lev 26:9-14 ; Jer 7:23 ; 30:22 ; 32:37-40 ; Ezek 11:19-20 ; 36:22-28 ; Acts 15:14 ; 2 Cor 6:16 ; Heb 8:10-12 ; Rev 21:3 ; etc.).Thus, the people of God are those in both the Old and New Testament eras who responded to God by faith, and whose spiritual origin rests exclusively in God's grace.

To speak of the one people of God transcending the eras of the Old and New Testaments necessarily raises the question of the relationship between the church and Israel. Modern theologies prefer not to polarize the matter into an either/or issue. Rather, they talk about the church and Israel in terms of there being both continuity and discontinuity between them.

Continuity between the Church and Israel. Two ideas establish the fact that the church and Israel are portrayed in the Bible as being in a continuous relationship. First, the church was present in some sense in Israel in the Old Testament. Acts 7:38 makes this connection explicit when, alluding to Deuteronomy 9:10, it speaks of the church (ekklesia [ejkklhsiva]) in the wilderness. The same idea is probably to be inferred from the intimate association noted earlier existing between the words ekklesia [ejkklhsiva] and qahal [l;h'q], especially when the latter is qualified by the phrase, "of God." Furthermore, if the church is viewed in some New Testament passages as preexistent, then one finds therein the prototype for the creation of Israel (see Exod 25:40 ; Acts 7:44 ; Gal 4:26 ; Heb 12:22 ; Rev 21:11 ; cf. Eph 1:3-14 ; etc.).

Second, Israel in some sense is present in the church in the New Testament. The many names for Israel applied to the church establish that fact. Some of those are: "Israel" ( Gal 6:15-16 ; Eph 2:12 ; Heb 8:8-10 ; Rev 2:14 ; etc.); "a chosen people" ( 1 Pe 2:9 ); "the true circumcision" ( Rom 2:28-29 ; Php 3:3 ; Col 2:11 ; etc.); "Abraham's seed" ( Rom 4:16 ; Gal 3:29 ); "the remnant" ( Rom 9:27 ; 11:5-7 ); "the elect" ( Rom 11:28 ; Eph 1:4 ); "the flock" ( Acts 20:28 ; Heb 13:20 ; 1 Peter 5:2 ); "priesthood" ( 1 Peter 2:9 ; Rev 1:6 ; 5:10 ). Discontinuity between the Church and Israel. The church, however, is not coterminous with Israel; discontinuity also characterizes the relationship. The church, according to the New Testament, is the eschatological Israel incorporated in Jesus Messiah and, as such, is a progression beyond historical Israel ( 1 Cor 10:11 ; 2 Cor 5:14-21 ; etc.). What was promised to Israel has now been fulfilled in the church, in Christ, especially the Spirit and the new covenant (cf. Ezek 36:25-27 ; Joel 2:28-29 ; with Acts 2 ; 2 Cor 3 ; Rom. 8 ; etc.). However, a caveat must be issued at this point. Although the church is a progression beyond Israel, it is not the permanent replacement of Israel (see Rom. 9-11, esp. Rom 11:25-27 ).

The Kingdom of God. Many scholars in this century have maintained that the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus inaugurated the kingdom of God, producing an overlapping of the two ages. The kingdom has "already" dawned, but is "not yet" complete. The first aspect pertains to Jesus' first coming and the second aspect relates to his second coming. In other words, the age to come has broken into this age and now the two exist simultaneously. This background is crucial in ascertaining the relationship between the church and the kingdom of God, because the church also exists in the tension that results from the overlapping of the two ages. Accordingly, one may define the church as the proleptic appearance of the kingdom. Two ideas flow from this definition: (1) the church is related to the kingdom of God; (2) but the church is not equal to the kingdom of God.

The Church and the Kingdom of God Are Related. The historical Jesus did not found or organize the church. Not until after his resurrection does the New Testament speak with regularity about the church. However, there are adumbrations of the church in the teaching and ministry of Jesus, in both general and specific ways. In general, Jesus anticipated the later official formation of the church in that he gathered to himself twelve disciples, who constituted the beginnings of eschatological Israel, in effect, the remnant. More specifically, Jesus explicitly referred to the church in two passages: Matthew 16:18-19 and 18:17. In the first passage, Jesus promised that he would build his church despite satanic opposition, thus assuring the ultimate success of his mission. The notion of the church overcoming the forces of evil coincides with the idea that the kingdom of God will prevail over its enemies, and bespeaks of the intimate association between church and kingdom. The second passage relates to the future organization of the church, particularly its method of discipline, not unlike the Jewish synagogue practices of Jesus' day.

The Church and the Kingdom of God Are Not Identified. As intimately related as the church and the kingdom of God are, the New Testament does not equate the two, as is evident in the fact that the early Christians preached the kingdom, not the church ( Acts 8:12 ; 19:8 ; 20:25 ; Acts 28:23Acts 28:31 ). The New Testament identifies the church as the people of the kingdom ( Rev 5:10 ; etc.), not the kingdom itself. Moreover, the church is the instrument of the kingdom. This is especially clear from Matthew 16:18-19, where the preaching of Peter and the church become the keys to opening up the kingdom of God to all who would enter.

The Eschatological Temple of God. Both the Old Testament and Judaism anticipated the rebuilding of the temple in the future kingdom of God (ez 40-48 Hag 2:1-9 ; 1 Enoch 90:29; 91:3; Jub 1:17, 29; etc.). Jesus hinted that he was going to build such a construction ( Matt 16:18 ; Mark 14:58 ; John 2:19-22 ). Pentecost witnessed to the beginning of the fulfillment of that dream in that when the Spirit inhabited the church, the eschatological temple was formed ( Acts 2:16-36 ). Other New Testament writers also perceived that the presence of the Spirit in the Christian community constituted the new temple of God (see 1 Cor 3:16-17 ; 2 Cor 6:14-7:1 ; Eph 2:19-22 ; cf. also Gal 4:21-31 ; 1 Peter 2:4-10 ). However, that the eschatological temple is not yet complete is evident in the preceding passages, especially with their emphasis on the need for the church to grow toward maturity in Christ, which will only be fully accomplished at the parousia. In the meantime, Christians, as priests of God, are to perform their sacrificial service to the glory of God ( Rom 12:1-2 ; Heb 13:15 ; 1 Peter 2:4-10 ).

The Bride. The image of marriage is applied to God and Israel in the Old Testament (see Isa 54:5-6 ; 62:5 ; Hosea 2:7 ; etc.). Similar imagery is applied to Christ and the church in the New Testament. Christ, the bridegroom, has sacrificially and lovingly chosen the church to be his bride ( Eph 5:25-27 ). Her responsibility during the betrothal period is to be faithful to him ( 2 Cor 11:2 ; Eph 5:24 ). At the parousia, the official wedding ceremony will take place and, with it, the eternal union of Christ and his wife will be actualized ( Rev 19:7-9 ; 21:1-2 ).

The Body of Christ. The body of Christ as a metaphor for the church is unique to the Pauline literature and constitutes one of the most significant concepts therein ( Rom 12:4-5 ; 1 Cor 12:12-27 ; Eph 4:7-16 ; Col 1:18 ). The primary purpose of the metaphor is to demonstrate the interrelatedness of diversity and unity within the church, especially with reference to spiritual gifts. The body of Christ is the last Adam ( 1 Cor 15:45 ), the new humanity of the endtime that has appeared in history. However, Paul's usage of the image, like the metaphor of the new temple, indicates that the church, as the body of Christ, still has a long way to go spiritually. It is "not yet" complete.

The Sacraments of the Church. At the heart of the expression of the church's faith are the sacraments of baptism and the Lord's Supper. The former symbolizes entrance into the church while the latter provides spiritual sustenance for the church.

Baptism. Baptism symbolizes the sinner's entrance into the church. Three observations emerge from the biblical treatment of this sacrament. First, the Old Testament intimated baptism, especially in its association of repentance of sin with ablutions ( Num 19:18-22 ; Psalm 51:7 ; Ezek 36:25 ; cf. John 3:5 ). Second, the baptism of John anticipated Christian baptism. John administered a baptism of repentance in expectation of the baptism of the Spirit and fire that the Messiah would exercise ( Matt 3:11 / Luke 3:16 ). Those who accept Jesus as Messiah experience the baptism of fire and judgment. Third, the early church practiced baptism, in imitation of the Lord Jesus ( Matt 3:13-17 / Mark 1:9-11 / Luke 3:21-22 ; see also John 1:32-34 ; cf. Matt 28:19 ; Acts 2:38 ; 8:16 ; Rom 6:3-6 ; 1 Cor 1:13-15 ; Gal 3:27 ; Titus 3:5 ; 1 Peter 3:21 ; etc.). These passages demonstrate some further truths about baptism: (1) baptism is intimately related to faith in God; (2) baptism identifies the person with the death and resurrection of Jesus; (3) baptism incorporates the person into the community of believers.

The Lord's Supper. The other biblical sacrament is the Lord's Supper, variously called "communion" ( 1 Cor 10:16 ), "eucharist" (the prayer of thanks offered before partaking of the elements Matt 26:27 ; 1 Cor 11:24 ), and the "breaking of the bread" ( Acts 2:42 ; 20:7 ). This rite symbolizes Christ's spiritual nourishment of his church as it celebrates the sacred meal. Two basic points emerge from the biblical data concerning the Lord's Supper. First, it was instituted by Christ ( Matt 26:26-29 ; Mark 14:22-25 ; Luke 22:15-20 ; 1 Cor 11:23-25 ). According to these passages, Jesus celebrated the Passover on the night before his betrayal. That commemorative meal would probably have included the following: the cup of wine, calling "blessing"; the four questions of the child concerning the nature of Passover; the second cup, called "deliverance"; the singing of the first part of the Hallel (Psalm 113-14); the Passover meal; the third cup, called "redemption"; the eating of the dessert; the fourth cup, called the "Elijah cup"; the singing of the second part of the Hallel (Psalm 115-18). Jesus introduced two changes into the Passover seder. He equated his body with the bread of affliction and his blood, which was to be shed on the cross, with the cup of redemption.

Second, the early church practiced the Lord's Supper ( Acts 2:42Acts 2:46 ; 1 Cor 11:23 ; etc.), probably weekly, in conjunction with the agape [ajgavph] feast (see 1 Cor 11:18-22 ; cf. Jude 12 ). A twofold meaning is attached to the Lord's Supper by the New Testament authors. First, it involves participation in Christ's salvation-believers are to "do this in remembrance of me" ( Luke 22:19 ; 1 Cor 11:24-25 ). A couple aspects of this celebration call for comment. (1) Historically, the Lord's Supper was a rite commemorating Christ's redemptive death, even as the Passover was a remembrance of God's deliverance of Israel from Egyptian slavery ( Exod 12:14 ; Exodus 13:3Exodus 13:9 ; Deut 16:3 ). In remembering Christ's death, believers actualize its effects in the present. (2) Eschatologically, the Lord's Supper anticipates Christ's return ( Matt 26:29 ; Mark 14:25 ; Luke 22:16Luke 22:18 ; 1 Cor 11:26 ) and, with it, the heavenly messianic banquet of the kingdom of God ( Matt 22:2-14 ; Luke 14:24 ; Rev 19:9 ).

Second, the Lord's Supper involves identification with the body of Christ, the community of faith. Two aspects of this reality are touched upon in the New Testament, one positive, the other negative. Positively, the Lord's Supper symbolizes the unity and fellowship of Christians in the one body of Christ ( 1 Cor 10:16-17 ). Negatively, to fail to recognize the church as the body of Christ by dividing it is to participate in the Lord's Supper unworthily and thereby to incur divine judgment ( 1 Cor 11:27-33 ).

The Worship of the Church. The ultimate purpose of the church is to worship God through Christ. The early church certainly recognized this to be its reason for existence ( Eph 1:4-6 ; 1 Peter 2:51 Peter 2:9 ; Rev 21:1-22:5 ; etc.). Five aspects of the New Testament church's worship can be delineated: the meaning of worship; the time and place of worship; the nature of worship; the order of worship; the expressions of worship.

The Meaning of Worship. Although the Bible nowhere provides a definition of worship, one is left with the general impression therein that to worship God is to ascribe to him the supreme worth that he alone deserves.

The Time and Place of Worship. Although many Jewish Christians probably continued to worship God on the Sabbath, the established time for the church's worship came to be Sunday, the first day of the week ( Acts 20:7 ), because Christ had risen from the dead on that day ( Rev 1:10 ). With regard to the locale, the early church began its worship in the Jerusalem temple ( Acts 2:46 ; 3:1 ; 5:42 ), as well as in the synagogues ( Acts 22:19 ; cf. John 9:22 ; James 2:2 ; etc.). At the same time, believers met in homes for worship ( Acts 1:13 ; 2:46 ; 5:42 ). When Christianity and Judaism became more and more incompatible, the house-church became the established place of worship ( Rom 16:15 ; Col 4:15 ; Phil 2 ; 2 John 10 ; 3 John 1:13 John 1:6 ; etc.). The use of a specific church building did not occur until the late second century.

The Nature of Worship. The biblical teaching on the worship of the church involves three components, which are rooted in the Trinity. First, worship is directed toward God; God the Father is the central object of worship, both as creator ( Acts 17:28 ; James 1:17 ; Rev 4:11 ; etc.) and redeemer ( Eph 1:3 ; Col 1:12-13 ; 1 Peter 1:3 ; Rev 5:9-14 ; etc.). Second, worship is mediated through Christ, the Son ( Matt 18:20 ; Rom 5:2 ; Eph 1:6 ; 1 Tim 2:5 ; Heb 4:14-5:10 ; 10:20 ; etc.). Third, worship is actualized by the power of the Holy Spirit ( Rom 2:28-29 ; 8:26-27 ; Eph 2:18 ; Php 3:3 ; Jude 20 ; etc.).

The Order of Worship. Both the language and the order of the early church's worship were rooted in Judaism. With regard to the former, the church utilized Old Testament terms like "high priest" (applied to Jesus, Heb 4:12-16 ), "priests" (applied to christians, 1 Peter 2:5-9 ), "sacrifice" (applied to Christ's death on the cross, Heb 9:23-28 ; 10:11 ), and "temple" (applied to the church, 1 Cor 3:16 ; 6:19 ). With regard to the order of worship, the early church incorporated into its worship the main elements of the synagogue service: praise in prayer ( Acts 2:42Acts 2:47 ; 3:1 ; 1 Thess 1:2 ; 5:17 ; 1 Tim 2:1-2 ; etc.) and in song ( 1 Cor 14:26 ; Php 2:6-11 ; Col 1:15-20 ; 1 Tim 3:16 ; Rev 5:9-10 ; etc.); the expounding of the Scripture ( Acts 2:42 ; 6:4 ; Col 4:16 ; 1 Thess 2:13 ; 1 Tim 4:13 ; etc.); and almsgiving to the needy ( Acts 2:44-45 ; 1 Cor 16:1-2 ; 2 Cor. 8-9 James 2:15-17 ; etc.).

Expressions of Worship. The main ingredient of worship in the Bible is sacrifice. David put it well: "I will not sacrifice to the Lord my God burnt offerings that cost me nothing" ( 1 Sam 24:24 ). In the New Testament, there are three main expressions connected with the worship of the early church, each of which is based on sacrifice: the sacrifice of one's body to God ( Rom 12:1-2 ; cf. Rom 15:16 ; Php 1:20 ; 2:17 ; 2 Tim 4:6 ); the sacrifice of one's possession for God ( Matt 6:2 ; Luke 6:38 ; 2 Cor. 8-9 1 Tim 6:10 ; etc.); and the sacrifice of one's praise to God ( Acts 16:25 ; 1 Cor 14:26 ; Eph 5:19 ; Col 3:16 ; Heb 13:16 ; James 5:13 ; etc.).

The Service and Organization of the Church. We conclude the topic of the biblical teaching on the church by briefly calling attention to its service and organization. Five observations emerge from the relevant data. First, the ministry of the church centers on its usage of spiritual gifts (charismata), which are given to believers by God's grace and for his glory, as well as for the good of others ( Rom 12:3 ; Eph 4:7-16 ; etc.). Second, every believer possesses a gift of the Spirit ( 1 Cor 12:7 ; Eph 4:7 ; etc.). Third, it is through the diversity of the gifts that the body of Christ matures and is unified ( Rom 12:4 ; 1 Cor 12:12-31 ; Eph 4:17-18 ). Fourth, although there was organized leadership in the New Testament church (elders, 1 Tim 3:1-7 ; [also called pastors and shepherds, see Acts 20:17Acts 20:28 ; 1 Peter 5:1-4 ; etc.] and deacons, 1 Tim 3:8-13 ), there does not seem to have been a gap between the "clergy" and "laity." Rather, those with the gift of leadership are called to equip all the saints for the work of the ministry ( Eph 4:7-16 ). Fifth, spiritual gifts are to be exercised in love ( 1 Cor. 13 ).

C. Marvin Pate

Bibliography. J. C. Beker, Paul the Apostle: The Triumph of God in Life and Thought; H. Bietenhard, NIDNTT, 2:789-800; L. Coenen, NIDNTT, 3:291-305; W. D. Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism; R. G. Hammerton-Kelly, Pre-Existence, Wisdom and the Son of Man: A Study of the Idea of Pre-Existence in the New Testament; H. Küng, The Church; G. E. Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament; P. S. Minear, Images of the Church in the New Testament; R. L. Saucy, The Church in God's Program; K. L. Schmidt, TDNT, 3:501-36; R. Schnackenburg, The Church in the New Testament; A. J. M. Wedderburn, Baptism and Resurrection: Studies in Pauline Theology against Its Graeco-Roman Background.

Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology. Edited by Walter A. Elwell

Copyright © 1996 by Walter A. Elwell. Published by Baker Books, a division of

Baker Book House Company, Grand Rapids, Michigan USA.

All is Welcome to this site to learn, to worship the name of JESUS!

Guess what there is no dress code here.

REALLY!

IT'S ALL ABOUT JESUS AND YOU!

THS STAR HAS

A

LINK FOR

SOAKING!

THIS A LINK TO WATCH WORSHIP VIDEOS!

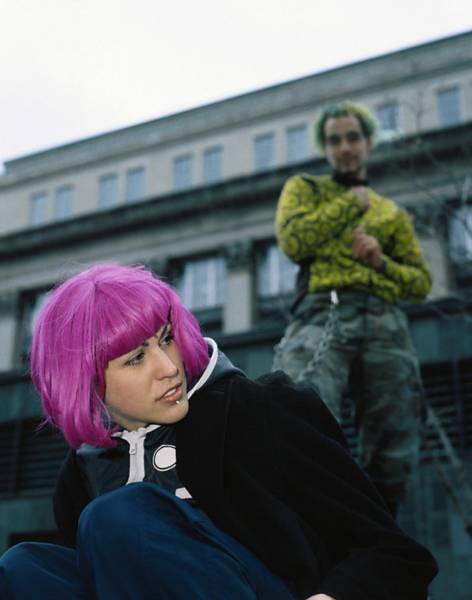

For my Gothic people here is a website that

I LOVE TO GO TO LEARN ABOUT JESUS.

BEING A CHRISTIAN AND BEING GOTHIC TOO.

Just click the black star to go to Christian Goth.com

Make sure you say Hello to Lady Michaela while your there.

Click here to read my favorite stories on Christian Goth.com